Anyone who has put their minds to Arabic will know that the initial major issue is WHICH Arabic to learn, classical or dialect and if dialect, which one. Do you study the written language you can find in books, or the daily conversation Arabic which has no written form?

As a parent, trying to open a little window, even a tiny porthole, onto the language and culture, this problem takes on a new form. I can read my kids books in French, normal everyday useful French. I can even read to them in Spanish, and apart from the rubbish accent it’s the same Spanish people really speak, more or less. But reading books in Arabic to your kids is rather weird. Because these simple sentences are things that no mother would ever say to her child. No-one actually speaks classical Arabic in any informal situation. And classical Arabic really is vastly different to the dialects in my unprofessional opinion. It even makes things complicated for native-speakers teaching their kids Arabic as a additional language.

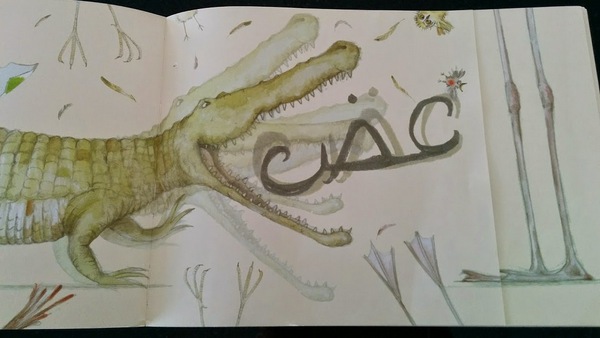

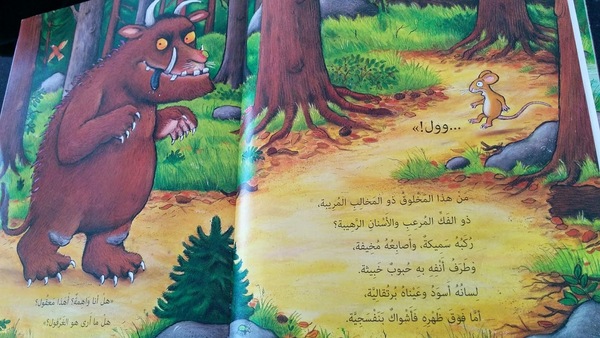

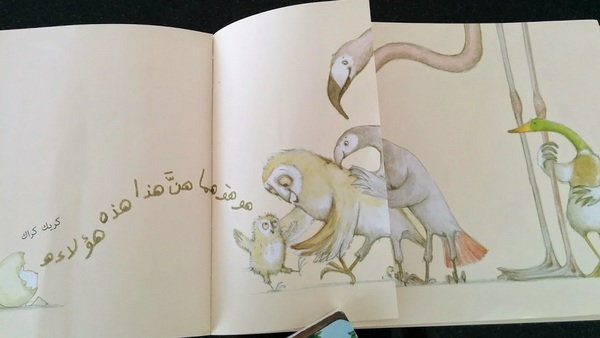

The result? No one reads my Arabic books to the kids. I thought people would quite like reading a story to the kids in Arabic and at the same time the kids would get some native input. So I pull out these lovely stories and they cuddle up on the sofa together, while I get on with preparing the dinner …only to hear Al Bayda Al Ajeeba (The Odd Egg) translated from Arabic into French. Or translated back into English. (Perhaps I should tape it and send it off to author Emily Gravett?) Not all my Arabic-speaking visitors do this automatic translation trick, but the majority. You’ve got to admire their linguistic flexibility.

It seems that the Lebanese are so unused to reading to kids in classical Arabic (let alone speaking it to them) that they naturally slip into other languages. And we mustn’t forget all the Francophile Lebanese who speak Arabic all day long in their daily lives, but only French to their kids.

No wonder many adult Lebanese find it such a drag to pick up a book in Arabic. They are not even used to children’s books in their native language (although I suppose classical Arabic doesn’t feel like their native language, and that’s the whole point). It’s a bit like French teenagers moaning about the ‘antiquated’ passé simple in French literature, but for Arabic it’s not just one verb tense which is no longer used in everyday language. It’s almost every part of speech.

While it is true that we could eliminate the French passé simple and just say the same thing in everyday French, I’m a bit of a romantic when it comes to language, so although it is more ornament than instrument, it doesn’t bother me. As for classical Arabic, it can’t be superseded as there is (as yet) no accepted written form of Arabic dialects (though I love the imaginative transliterated dialect I read online). More importantly, classical Arabic crosses the borders of the many Arab countries. That’s quite a sacrifice if you decide to opt for just one spoken dialect.

All the heavy debate aside, I just love to watch my 3-year old bouncing up and down on the terrace shouting “Wain el ‘amar?” (where’s the moon?) to her little brother who nearly falls over himself pointing and shouting “Amar! Amar!” (moon! moon!). Later they’ll have to learn that it is written something like “Ayna el qamar?” but for now I’m chuffed as it is.