I’m really not very patient with languages. I do like them, but being bad at them is not a stage I enjoy. I have been on a plateau for the past year. Any improvement has been unnoticeable. Now, with one of my two little ones in school, I finally have time to learn properly, and I want to learn fast. So this is my plan. Feel free to share your language learning plan, too.

Step one: Enrol in classes

Technically I should be able to get my oral practice from the neighbours and my grammar from the books, but I find classes a real motivation, and you do learn from others’ mistakes as well as your own. I’ll be aiming to get my money’s worth by taking the teacher all the awkward questions that come into my head between lessons.

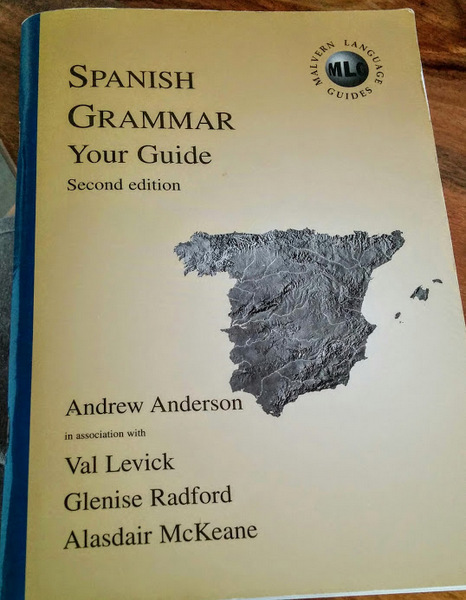

Step two: Use a good grammar guide

Not a textbook, just a go-to guide with an irregular verb table and the grammar rules spelt out. A guide like this keeps different tenses and other concepts in their places.

Step three: Use every opportunity to talk

Even though I am living in Spain, at my level of non-fluency, these opportunities arrive and then disappear very fast. Once you’ve greeted some acquaintance, like the other mums at my daughter’s school, the conversation can either tail off or get interesting. Most of my conversations tail off very quickly. Even in a shop, you can either get by with a few words and gestures, or you can find the accurate way to ask for what you want and include some details. To try to get more practice, I have started planning what to say in situations that I know are coming up – the doctor, teacher, shops, anything. Since you actually do use what you plan, it gets embedded in your memory; it’s way more effective than memorising vocabulary for some theoretical future use.

Jumping on opportunities also means accepting to use very, very basic language to start a conversation, or even asking a question you think you probably already know the answer to, just to get things started. Hey, at least if you’re right then there’s a fair chance you’ll understand the answer. It’s tough having to look stupid to all these new people you’re actually trying to make a good impression with, but I figure I’ll feel cleverer when I can actually speak Spanish.

Step four: Work at home

Or in a café. But on my own (that is, with the baby), going through the class notes, revising new vocabulary, looking up any words I wanted to say but couldn’t think of, checking my grammar guide for the right way to conjugate some verb, or to form some tense. Also talking with friends about my language questions, as well as things I’ve just learnt. Teaching others is one of the best forms of repetition for a learner, so make sure to tell someone the new stuff you come across. I try everything out on my husband, who fortunately also wants to learn. When I was learning French I would revise classes with a fellow student afterwards.

Step five: Read for pleasure

Roald Dahl, here I come again. The local library has a few translated Roald Dahl books marked 10 years and over. They are just the right level for me. You want to find books where you can understand the story without a dictionary, or else it’s too slow to be motivating. When you meet unknown words you can guess, look them up, or skip them. Dahl’s books are good because I have vague memories of the storyline from, um, about 20 years ago. But it would be better to have books originally written in Spanish, I just haven’t had time to scour the library shelves and find the right level along with a good read. Reading isn’t just about books; packaging labels, newspaper headlines, adverts, posters and graffiti – they all count. I still remember the satisfaction of finally understanding the cultural references and bad puns in slogans on the billboards in the Paris metro stations.

Step six: Pay attention to culture

This comes in conjunction with all the other steps (that’s why Roald Dahl isn’t as good as native Spanish options, but it’s better than nothing). This is more than knowing the stereotypes. There’s a difference between knowing that the Spanish have a late lunch and knowing that the builders are going to disappear at 12 noon for something they call desayuno. See below for more.

Men called Maria

I already knew that all Spanish women of a certain age seem to have Maria as part of their name. When I had to find which parent was collecting the school supplies fee, and asked one of the other mums, I didn’t get all of her response. I understood it was “Maria” who was standing over there wearing a “camiseta gris”. I couldn’t see a mum in a grey top at all. “Con las gafas?” I asked, but she said no, dark hair, no sunglasses. The only one I could see with dark hair and no sunglasses had a pale blue top on. I wondered if the mum helping me was colour blind since she was definitely pointing that way. So tentatively I approached the blue top lady. Only to have a guy come over and introduce himself as José Maria and offer me a receipt for the fee. The penny finally dropped. Thinking of Maria as a woman had blinded me to his grey T-shirt. I should have known this, as France has its own share of men called Jean-Marie and the like, but they are usually not the same generation as me (think: Le Pen). The moral of the tale? Knowing what to expect is half the hard work.