This my second vuelta al cole in Spain, the second time I have been here at the start of a new school year, when summer winds down, temperatures become pleasant, and town gets quiet.

The first was a non-event as nobody in our family went to school, to the surprise of our neighbours. This time round has been quite different with my four-year old now officially escolarizada, which actually meant braving the seasonal flurry of stationery to buy books (for preschool!). She wasn’t the only one. I am now enrolled in the Casa de la cultura for Spanish lessons twice a week, as I attempt to keep up with my daughter as long as I possibly can!

This is the third time I have moved to a new country and thrown myself into learning the local language. But this time is more complicated than the previous two.

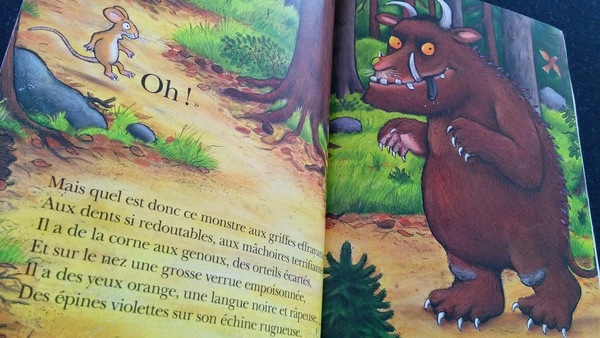

The first time was the simplest: I moved to Paris and immediately started a French degree. I knew a lot of other English students but I did plenty of activities in French, listened only to French radio, wrote all my notes in French, and read constantly in French. I had no internet at home for the first two years, so no BBC Radio, no English TV, no Skyping family all the time. Instead of looking things up on the Web I had to find everything out from the locals. It was true immersion.

The second time was in Lebanon. I started lessons after a few months. Lebanese is a harder language to break into, as there’s no real written form of it. But by the end of three years I could understand most of what went on, even in fast-moving social situations. However, meetings and the radio were still very hard. I also had my work (in French and English) and soon a baby to take up my time, as well as other priorities.

This time round is the longest I have left it before starting any classes. I’ve spent the last year and a half in a bubble. I speak Spanish every day, but only the smallest of small talk, buying the veg, other mums at the park, neighbours in the stairwell. I have a few Spanish friends who speak reasonably good English. Life is too busy for me to go out looking for new friends just because they are Spanish. However, this time round there are also some advantages. The local language seems so much more accessible. Unlike Arabic, you say everything like you write it (albeit at top speed). Plus it is so similar to French. I’m not just talking about words like timide (FR) and tímido (ES – shy). Even phrases like no vale la pena (it’s not worth it), and hacerse pasar por (pretend to be) are so similar in form to the French equivalents ça ne vaut pas la peine, and se faire passer pour.

There wasn’t a placement test for the classes at the Casa de la cultura. The secretary just enrolled me in the A2 level. From what I can tell, A1 is for absolute beginners, A2 for basic tourism, B1 for actually communicating, B2 for competency, C1 for fluency and C2 for mastery.

When I got home and researched the levels, I decided A2 could be a bit slow. I know there will be stuff in it that I don’t know – in fact there’s probably a fair bit in A1 I don’t know yet. But with a kid in school, I am now officially out of my bubble. Not only do I have to talk to her teacher and to the other parents, I have more time to talk to everybody I meet all week, and more time to learn on my own. Also I know the past tenses, the future, the conditional and the subjunctive, when I see them. And I’m willing to work at it because I’m impatient to be able to communicate.

So I tried the online tests, which I passed, up to and including B2. I’ve always been better on paper than in real life. Sad, but true. In fact, when I sat a similar placement test for Classical Arabic lessons years ago, I asked the teacher to enter me into a lower level than the one I qualified for, and the class I ended up in was plenty hard enough. There I was at a disadvantage there compared to many of the other students. Most were of Arab origin, so that gave them some background knowledge, concrete examples they knew were right, and a bunch of random vocabulary they could call in to play. This time I don’t feel any such disadvantage, as most foreigners here are English or Scandinavian or Dutch and can’t call on any knowledge of Latin languages. So I have been swotting up on my conjugations in the hope the Casa de la cultura will bump me up a level when I start.

From now on I’ll be sharing what I learn here. I figure it makes an extra outlet to ease the avalanche my husband faces every time I come in the door, spouting all the expressions and grammar explanations I’ve learnt! For now, here is a bit of vocab from the scolastic baptism of fire.

la mochila – back pack, specifically at my school they want them to be sin ruedas, without wheels, so none of this small suitcase business

la vuelta al cole – the back-to-school period or start of the school year

el cole = short for colegio – primary school …NOT British college (16-18y), not French collège (11-15), and not US college (18+). After el colegio comes instituto – secondary school

infantil – the preschool section for ages 3 to 5

la maestra – teacher, or of course el maestro if you have a male teacher

el desayuno – breakfast of course, however my school papers say the children must have desayuno before school but also bring desayuno with them in their mochila to eat before el recreo (break). So elevenses, or playtime snack, or tuck if you like. Le goûter for the French, but at the wrong time.