At the beginning of the summer, we came across The Very Hungry Caterpillar at the local library, the Spanish version. Curled up on the sofa with my nearly-four-year old, I read it in Spanish, pausing when I think she can fill in a word she knows, like luna (moon) or hambre (hungry). After all, in September she starts school – 100% Spanish school.

When I get to hoja (leaf), I pause, thinking she might know it. She suggests “feuilla?”, her own variation on the French word feuille. She’s completely wrong, but I’m pleased all the same. Clearly she has seen how similar French and Spanish are. Most of the time at least, even if not for the word leaf.

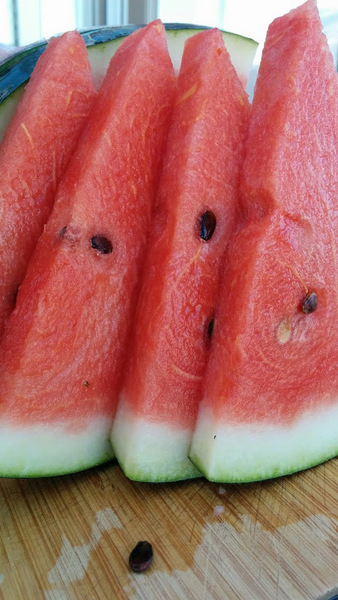

When the caterpillar goes on a major binge on Saturday before building its chrysalis, I pause for her to guess at a couple of food items, like ‘queso‘ (cheese) which she gets right. The last thing the caterpillar eats on Saturday is ‘un trozo de sandía‘, a slice of watermelon. When I pause tentatively, my daughter suggests: ‘pastequa?’ from the French pastèque.

Learning Spanish naturally pushes you to draw on French or any other Romance language you may have some grounding in because of so much vocab in common. In addition, some grammar is more understandable to English eyes, for example, Spanish has two present tenses, giving equivalents to I do and I am doing whereas French only has one, je fais. And to top it all off, Spanish has a large vocabulary of words taken from Arabic, though many are altered past recognition. In fact, Arabic is said to be the second largest lexical influence on Spanish, after Latin, accounting for 8% of the Spanish dictionary.

So with some knowledge of French, English and Arabic, I feel we should be able to get to the bottom of Spanish. Except of course there are some words which, at first, seem to have come from nowhere. Like hoja (leaf/feuille), for instance. Or hogar (home/chez soi). They don’t seem to have anything in common with their French, English or Arabic equivalents. It feels a bit odd, when words come from nowhere, because that’s just not possible. But then I noticed a pattern between Spanish and French.

Hoja – feuille (leaf)

Hija – fille (daughter)

Higo – figue (fig)

Hinojo – fenouil (fennel)

Hambre - faim (hungry)

Hilo – fil (thread)

Hila – file (row, queue)

Harina – farine (flour)

Hogar – foyer (home)

There’s definitely a shift from the initial F in Latin to H in Spanish. And I’d say there’s some kind of complicity between the L and the Spanish J – someone out there who’s done some Spanish linguistics would know. All of a sudden the fog clears and hoja does look a bit like feuille, or at least like folio and its variations. And while hogar can’t be made to resemble chez, it happens to share its root with foyer (from the Latin focus, or fireplace; and of course hogar and foyer also mean hearth). Even hacer, a word I learnt so long ago I never wonder about its origin, is apparently a cognate of faire.

I even came across a Spanish sign asking people not to fumar (smoke, French: fumer) as we were in un espacio sin humo (smoke-free area, in French literally un espace sans fumée). So there you have both spellings in the same word group. Once you’ve got the pattern, all sorts of words make sense and become easier to learn. Now I know an F can hide an H just like J can replace an X, or like the German J often turns out to be a Y in English. The language nerd inside me is relieved, triumphant even; it does make sense after all.

Funnily enough, it turns out sandía is from an Arabic word, but not the one I know, bateekh بطيخ , which is, however, the one which pastèque comes from. Sometimes with etymology you seem to end up right back where you started.